Executive Summary

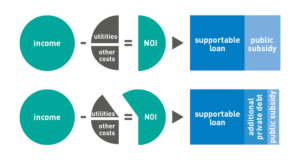

Building to the Passive House design standard reduces operational costs, which can offset incremental costs of construction and create additional, ongoing cash flow.

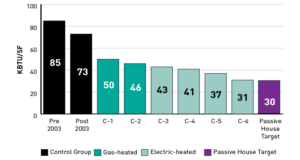

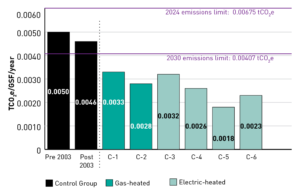

This playbook analyzes energy use, emissions, and operational cost data from six New York City multifamily Passive House buildings and compares it against data from their conventionally built peers. Findings show that the Passive House buildings use far less energy than typical multifamily buildings. These results translate into operational cost savings that can increase access to private debt and may also decrease reliance on public subsidies for certain types of affordable housing. Passive House buildings also emit significantly less carbon than conventional buildings, which may enable them to avoid civil penalties related to carbon regulations.

This study was a collaboration between the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development (NYC HPD), The Community Preservation Corporation (CPC), Bright Power, and Steven Winter Associates (SWA).